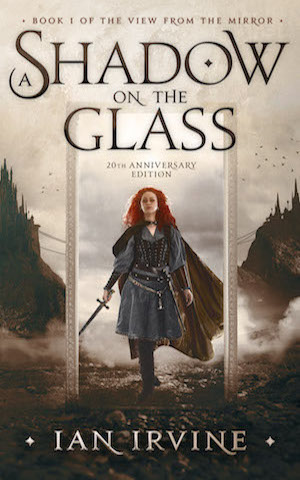

Book 1: The View from the Mirror

Chapter 1: The Tale of the Forbidding

It was the final night of the Graduation Telling, when the masters and students of the College of the Histories at Chanthed told the Great Tales that were the very essence of human life on Santhenar. To Llian had fallen the honour and the peril of telling the greatest tale of all – the Tale of the Forbidding. The tale of Shuthdar, the genius who made the golden flute but could not bear to give it up; who had changed the Three Worlds forever.

The telling was perilous because Llian was from an outcast race, the Zain, a scholarly people whose curiosity had led them into a treacherous alliance in ancient times. Though their subsequent decimation and exile was long ago, the Zain were still thought ill of. No Zain had been honoured with a Graduation Telling in five hundred years. No Zain had even been admitted to the college in a hundred years, save Llian, and that was a curious affair in itself.

So, his tale must best them all, students and masters too. Succeed and he would graduate master chronicler, a rare honour. No one had worked harder or agonised more to make his tale. But even a perfect telling would bring him as many enemies as admirers. Llian could sense them, willing him to fail. Well, let them try. No one knew what he knew. No one had ever told the tale this way before.

Once there were three worlds, Aachan, Tallallame and Santhenar, each with its own human species: Aachim, Faellem and us, old human. Then, fleeing out of the void between the worlds came a fourth people, the Charon. They were just a handful, desperate, on the precipice of extinction. They found a weakness in the Aachim, took their world from them and forever changed the balance between the worlds.

The Great Tales all began with that introduction, for it was the key to the Histories. Llian took a deep breath and began his tale.

In ancient times Shuthdar, a smith of genius, was summoned from Santhenar by Rulke, a mighty Charon prince of Aachan. And why had Rulke undertaken such a perilous working? He would move freely among the worlds, and perhaps the genius of Shuthdar could open the way. So Shuthdar laboured and made that forbidden thing, an opening device, in the form of a golden flute. Its beauty and perfection surpassed even the dreams of its maker – the flute was more precious to him than anything he had ever made. He stole it, opened a gate and fled back to Santhenar. But Shuthdar made a fatal mistake. He broke open the Way between the Worlds …

The tale was familiar to everyone in the hall, but the crowd were silent and attentive. Llian did not relax for a moment. The story was hours long, and before it was done he would need every iota of his teller’s voice, that almost magical ability of great talesmiths to move their audience to any emotion they desired. It was an art that could not be taught, though the masters tried hard enough.

Llian met the eyes of the assembly, one by one, as he told the tale. Everyone in the room knew that he spoke just to them.

The opening shocked Aachan, that frigid world of sulphur-coloured snow, oily bogs and black luminous flowers, to its core. The Charon hunted Shuthdar to Santhenar, bringing with them a host of Aachim, that they had enslaved at the dawn of time. All came naked and empty-handed, for any object taken from one world to another might mutate in treacherous ways. The Charon must leave behind their constructs, mighty engines of transformation or destruction, and rely on older powers.

And Tallallame, its rain-drenched forests and towering mountains the antithesis of Aachan, was also threatened by the opening. The Faellem, a small, dour folk for whom the universe was but an illusion made by themselves, selected their best to put it right. Faelamor it was who led them so proudly to Santhenar. Neither did they bring any weapons. Their powers of the mind were such that on their own world they needed nothing more.

Shuthdar was hunted across the lands and down the grinding centuries, fleeing through gate after gate, and wherever he went he brought strife. But finally he was driven into a trap …

At last Llian came to the climax of his long, long tale, the part that would turn the Histories upside down. He took a deep breath, searching the faces for a sign that they were with him. The longing for their approval was a physical ache. But they were a true Chanthed audience, both reserved and highly critical. They would give nothing until they had judged the whole.

In his prime, using the stolen flute, Shuthdar could escape any enemy. But he had lived to a tremendous age, his very bones had shrunk and twisted, his once clever hands were no more use than paws. Now he was trapped and he knew it was the end. Sick with fear and self-loathing he huddled under a log in a scrap of forest, clawing out beetles and roaches and snapping them up, more a hyena than a man.

Only now as he looked back over his epic life did Shuthdar realise where he had gone wrong. It was not enough that he had been the greatest craftsman of his age, or any age. No, he must gloat over the priceless treasure that he had, that only he could have made, that had changed the face of the Three Worlds. There were times he would boast aloud, when there was no one to hear. But even the inanimate earth had ears for such a secret and his enemies always found him again. For half a millennium they had hunted him across Santhenar. Now they were all around and he had no will to defy them.

As he spoke Llian scanned the stolid figures, searching for a crack in their reserve, something to inspire him to that ultimate peak of the storyteller’s art. He was sure that they approved of the telling so far; but would they accept the new ending? And then he found what he was looking for. At the back he made out a single pale face in the crowd, a young woman staring at him so hard that it burned. He had moved one person, at least. Llian used all the magic of his voice and spoke directly to her.

Shuthdar squinted out between the trees. Before him, on a promontory extending like a finger into the great lake, the rising sun illuminated a tower of yellow stone. As good a place as any to end it.

He crashed through an archway, terrifying a family eating at a square table. Shuthdar bared ragged iron teeth, corroded things that mocked his once exquisite craftsmanship. His mouth was stained rust-red. It looked as if he had dined on blood.

Children screamed. A meagre man fell backwards off his chair. Shuthdar glared at them, his misshapen face twisted in a grimace of pain. Crab-like on writhen legs he scuttled past. Chairs, dishes, infants all went flying. A fat woman flung a tureen at his head, snatched a baby from the floor and the family fled, abandoning the crippled girl hidden away upstairs.

Shuthdar licked a spatter of soup from his hand, spat red saliva over the rail and dragged himself to the top of the tower.

At the sight of him the crippled girl put her hands up over her mouth. With yellow skin drum-tight over his cheeks, shrunken lips drawn back so that the rusty teeth and red-stained gums were vivid, he looked like the oldest, ugliest and most dissipated vampire that can ever be imagined. Pity the forsaken creature, if you will.

They faced each other, cripple and cripple. Black hair framed a pretty face, but her legs were so withered that she could barely walk. Time was when he would have despoiled her pitilessly, though that part of him had dried up long ago. Once he might have cast her off the tower, delighting in his power and her pain, but not even cruelty gave him pleasure any more.

“Poor man,” she sighed. “You are in such pain. Who are you?” Her voice was gentle, concerned.

“Shuthdar!” he gasped. Red muck ran down his chin.

She paled, groping behind for the support of her chair. “Shuthdar! Do you come to plunder me?”

“No, but you will die with me nonetheless.” He pointed to the forest, now a semicircle of flame centred on the tower. “No one has more enemies than I do,” he said, and knew how pathetic was his pride. “See, already they come, burning all before them. Are you afraid to die?”

“I am not, but I have so many dreams to live.”

His laughter was a mocking howl. “I know the only dreams a cripple can have – misery and despair! Even your own family locked you away so you would not shame and disgust them.”

She let go of the chair and drew herself up, like a queen in her dignity, but her cheeks were wet with tears. To his astonishment, Shuthdar the monster, the brute, was moved to compassion.

“What is your dream?” he asked tenderly, a new emotion for him. “I would grant you that before we die, should it be in my power.”

“To dance,” she replied. “I would dance for the lover of my dreams.”

Without a word he snapped open the case that he carried and there was revealed the golden flute. No more perfect instrument was ever made.

He put it to his bloody lips and played. His ruined hands were in agony but his face showed none of it. His music was so haunting, so beautiful that her ancestors rattled their bones in the crypt below the tower.

The crippled girl took a step, looking up at Shuthdar, but he was staring into another world. She tottered forward in a mocking travesty of a dance, clubbing the stone with her feet. She began to think that he played the cruellest joke of all, that she would crash on her face to his brutal laughter. Then suddenly the music picked her up and bore her away, and the torment in her limbs was gone, and her feet went just where she wanted them to. She was as light in her slippers as any belle, and she danced and danced until she could dance no more and fell to the floor in a cloud of skirts, all flushed and laughing, too exhausted to speak. And still Shuthdar played, till she was carried far off into her dreams and all her present life was forgotten.

The music slowly died away. She came back to herself. Shuthdar seemed lit up from within, all his ugliness burned out. He lowered the flute and wiped the ruby stains lovingly from it.

“They come,” he said gruffly. “Go down, wave a blue flag from the doorway. There is a chance they will let you pass.”

“There is nothing out there for me,” she replied. “Do what you must.”

For an instant Shuthdar thought that he did not want to die after all, but it was far too late for that.

The audience sighed audibly – another sign! The Histories were vital to Santhenar, and no one, great or small, was untouched by them. The highest honour anyone could wish for was to be mentioned there. Llian knew what the masters and students were thinking. Where had he found this new part of the tale that turned Shuthdar’s character inside out? The Great Tales were the very core of the Histories; tamper with them at your peril. He would have to prove every word of it tomorrow. And he would.

Llian looked down into the crowd, and out of the impassive hundreds his gaze was caught by that pale face again. She was concealed by cloak and hood, though from the front of the hood peeped hair as red as a plum. She was leaning forward, utterly rapt. Her name was Karan Elienor Fyrn and she was a sensitive, though no one in the hall knew it. She had come right across the mountains to hear the tales. Llian’s eyes met her eyes and she started. Remarkably, she broke through his concentration and for a second their minds touched as though they were linked. Llian was moved by her impossible yearning but he wrenched away. He had worked four years for this night and nothing was going to distract him.

He dropped his voice and saw the crowd inch forward in their seats, straining to catch his every word. He felt reassured.

Shuthdar’s enemies crept closer. The great of the Three Worlds were there, four human species. There were Charon and Aachim and Faellem; the best of our kind too. Rulke was at their head, desperate to recover the flute and to atone for the crime of having had it made in the first place.

Shuthdar watched them with his blanched eyes. There was no hope – his life was over at last. Soon the flute would pass to another. Death he welcomed, had long wished for, but he would not even think of the flute in another’s hands.

And so, as they drew near, he stood up on the top of the wall, outlined against the ghastly red moon, the deep lake behind and below. The crippled girl cried out to him but Shuthdar screamed, “Don’t move!” He lifted the flute in one claw of a hand, cursed his enemies and blew a despairing, triumphant blast.

The flute glowed red. The air gleamed with luminosity. Birds fell dead out of the sky. Rainbow waves fled out in all directions and flung the watchers into insensibility. The tower fractured and Shuthdar toppled backward and smashed on the hard dark water far below. The earth was rent and the waters of the lake leapt up and broke over the ruins.

Some say that the glowing flute fell, faster than Shuthdar, into the deep water, sending up a great cloud of steam and boiling the water until at last it was quenched in the icy depths and perhaps lies there still, buried in the slowly deepening mud; preserved forever, lost forever. Others said that they saw it melt and turn to smoke in the air and vanish, consumed by the forces trapped within it long ago.

Others yet held that Shuthdar had tricked them again, escaping to some distant corner of Santhenar where no one knew of him; or even into the void between the worlds, out of which came the desperate Charon to take the world of Aachan in ancient times. But that is surely not so, for two days later the waters cast back his shattered corpse in all its hideousness onto the rocks not far from the tower.

The tale was well told but the audience had expected more. They began to fidget and murmur. But Llian was not yet finished.

Shuthdar was lost, the golden flute too. The broken tower was a nightmare of fumes and radiation, save for a protected space where the girl lay, unharmed. Spectres walked the glowing walls, her heartless ancestors. The crippled girl wept, for her dreams were gone forever. Then she thought to tell the tale, to have a precious memento of this day, and to put a small white mark on the black stain that was Shuthdar’s reputation; the most reviled man on Santhenar.

But as she finished her writing the world twisted inside out. Splinters of solid light seared her eyes. The sky began to shred itself into drifting flakes. The tower shivered; the rubble shifted like rubber blocks, then a gate burst open above the ruins with a flare like a purple sun, and she looked into the void between the worlds.

Shadows appeared in the brilliant blackness. An army swarmed behind the gate, creatures out of horror. The void teems with the strangest life imaginable, and existence there is desperate, brutal and fleeting. In the void even the fittest survive only by remaking themselves constantly, and every being there is consumed by a single urge – to escape!

Now the crippled girl saw that creatures out of legend did battle beyond the gate, struggling to get through. The whole world was in peril. Nothing could withstand this host.

Her legs were too painful to walk. Terrified, she dragged herself in among the rubble and hid. Then, as the sun stood nearly to noon, a cloaked spectre separated out of the mass of ghosts that still swarmed over the tower. At first she thought it was her Shuthdar, restored to the flower of his youth, for the hooded figure was tall and dark.

The spectre moved its arms over a fuming crater in the stone. Immediately it was attacked by carmine lightning that sizzled out of the gate. Ghost-fire outlined its cloak. Beneath its feet the stone suddenly flowed like water, dragging the spectre down into the crater. The air reeked of brimstone, then it conjured a shimmering protection out of the turmoil, a cone of white radiance that hung the gate with a cobweb of icicles, a Forbidding! The gate boomed shut and vanished.

The crowd sat up in their seats. This was controversial, for the Histories told that the Forbidding came about by itself. If it had been made, it raised all sorts of possibilities. Yet Llian knew that it would take more than visions to convince this audience.

The audience began to stir uneasily. The tale was practically done but no proof had been offered. They felt let down. Llian drew out the moment.

And the girl? They found her too, when it was safe to go within, later that afternoon. A remarkably pretty young woman, she was crumpled up on the stone with the long skirt covering her sad legs. She was smiling as though she had just had the most wonderful day of her life. Strangely, among all that destruction the girl seemed to have taken no harm, but she was quite dead.

Anxious to mend Shuthdar’s evil record, she had written down his tale, put it in her bodice, then thrust a long hat-pin right through her heart.

This caused a sensation! Llian held up his hand and showed two papers, one blotched with a rusty stain.

I have the proof right here, sealed with her own heart’s blood.

So ends the Tale of the Forbidding – the first tale and the greatest.

The whole room was on its feet but no one made a sound. They were trying to work out the implications. Then the crowd took a collective breath – the black-robed masters were filing down the hall, two by two, and up the centre steps to the stage. Llian’s uncertain smile froze on his face. He had never wanted more than to be a chronicler and a teller. Had he failed so badly as to be publicly stripped of even his student’s rank?

Wistan, the master of the college, a little man almost as ugly as Shuthdar himself, had always detested Llian. He stood right in front of him, yellow eyes bulging out of a face like a bowl.

“A remarkable story. But it was not in the proofs you gave me,” he rasped.

“I kept these back,” Llian replied, clutching his documents like a lifebelt.

Wistan held out a desiccated hand. Llian dared to hope. “The second paper certifies the girl’s story,” he added softly.

Wistan scanned the papers. The folds of the first were perforated through and through, the mark of the fatal pin. His face grew greyer and greyer. “So it is true,” he sighed. “Even now such knowledge could be deadly. Say no more!”

Llian’s knees were shaking so much that he almost fell down. Wistan was a study in indecision. The telling had been a marvellous one, but it threatened everything he had ever worked for. Then the assembled masters forced his hand. They gave a great cry as of one throat, surged forward, bore Llian up and carried him across the stage in triumph. The whole room was laughing and crying, cheering and throwing their hats in the air. Nothing like this had ever happened before. Wistan followed them reluctantly.

As they swayed across the room toward the exit, Llian caught sight of the red-haired woman again, staring at him. She tried to force her way through the crowd and once more he felt that extraordinary sensation, as though their minds were linked. Who was she? The Graduation Telling was closed to the public but she was not from the college – he had never seen her before.

She almost reached him, getting so close that he caught a whiff of her lime-blossom perfume, then the crowd forced them apart. Her lips moved and he heard in his head, “Who killed her?” then she disappeared in the m;afel;aaee and he was carried out of the hall to the celebrations.

But much later, rolling home down the cobbled street surrounded by friends as merry as he was, her words came back to trouble him. The apparent suicide had always puzzled him, but how could anyone else have gotten into the ruins unobserved? Nonetheless the question had been raised and it would not go away. What if someone had found something so important that the girl had to be silenced? That could be the key to an even better story – the first new Great Tale for hundreds of years, and if he were the one to write it, he would stand shoulder to shoulder with the greatest chroniclers of all time. Consumed by this thought, Llian forgot all about Wistan’s caution.

“Look!” cried his friend Thandiwe, a tall handsome student. She and Llian had been friends for years, and occasionally lovers too. She was pointing toward the horizon. “A new star. That’s an omen if ever I saw one. You’re going to be famous, Llian.”

Llian’s gaze followed her finger. It was not a star at all, but a nebula, for it had a definite shape. A dark-red blotch that he had never seen before, like a tiny spider. Suddenly Llian felt cold though it was a warm summer’s night.

“An omen. I wonder what kind of an omen? I’m going to bed.”

“I’m coming too,” said Thandiwe, embracing him and tossing the waterfall of her black hair so that it covered them both.

Before dawn a dreadful realisation woke Llian so abruptly that he fell right out of bed. It was so obvious that he was amazed he hadn’t thought of it himself. If the girl had been murdered, the record he had used for his tale might be false. And if it was, his career would be ruined beyond redemption. There was no more honoured profession than chronicler, but no one would be more scorned than he who had debased the greatest of all tales.

Thandiwe sighed and snuggled down under the covers. Llian picked himself up off the floor and gathered a blanket round him, shivering and staring out the window. The nebula was high, seemingly bigger than before, and now that he saw it clearly Llian realised that it had not the form of a spider at all, but its more deadly relative, the scorpion.

Fame or oblivion? Either way he had to find the truth. Who had killed the crippled girl? And why? And how could he possibly find out, after all this time?